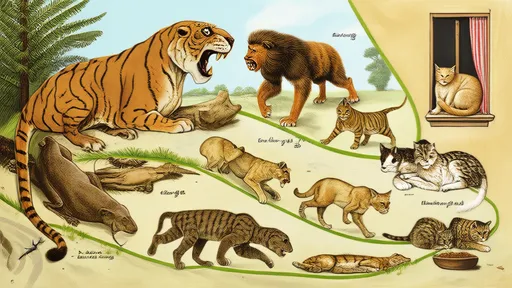

The evolutionary journey of felids, from the formidable saber-toothed cats to the domesticated house cats, represents one of nature's most fascinating dietary adaptations. Over millions of years, these predators have undergone significant changes in their hunting strategies, prey preferences, and physiological traits, all driven by the relentless pressures of survival and environmental shifts. The story of their dietary revolution is not just about what they ate but how their entire biology transformed to meet the demands of a changing world.

Saber-toothed cats, such as the iconic Smilodon, were apex predators of the Pleistocene epoch, renowned for their elongated, blade-like canines. These fearsome weapons were perfectly adapted for delivering devastating killing bites to large, slow-moving herbivores like mammoths and ground sloths. Their robust limbs and powerful necks suggest an ambush-based hunting strategy, where they would overpower their prey with sheer force rather than endurance. The diet of these ancient felids was heavily reliant on megafauna, a resource that would eventually vanish, contributing to their extinction.

As the megafauna disappeared, the felid family faced a critical crossroads. Smaller, more agile species began to dominate, shifting their focus from large, cumbersome prey to quicker, more abundant animals like rodents, birds, and reptiles. This transition marked the beginning of a dietary revolution that would eventually lead to the emergence of modern felids. The reduction in body size and the development of retractable claws, keen night vision, and heightened auditory senses were all evolutionary responses to this new hunting paradigm.

The domestication of cats around 10,000 years ago further altered their dietary habits. Unlike dogs, which were actively bred for specific tasks, cats likely domesticated themselves by capitalizing on the rodent populations thriving in early human settlements. This symbiotic relationship allowed cats to maintain much of their wild dietary preferences while benefiting from the safety and surplus of human environments. Even today, the domestic cat retains a strong instinct for hunting, a testament to its evolutionary heritage.

Modern house cats, though often fed processed commercial diets, still exhibit behaviors and physiological traits rooted in their carnivorous ancestry. Their short digestive tracts, high protein requirements, and inability to synthesize certain essential nutrients from plant matter underscore their obligate carnivore status. The dietary revolution from saber-toothed megafauna hunters to small-prey specialists and, finally, to human-associated hunters reflects the remarkable adaptability of felids across millennia.

Understanding this evolutionary trajectory not only sheds light on the biology of modern cats but also offers insights into the delicate balance of ecosystems. The extinction of saber-toothed cats serves as a stark reminder of how vulnerable even the most specialized predators can be when their food sources disappear. Meanwhile, the success of smaller felids highlights the advantages of dietary flexibility in a rapidly changing world. From the ice age giants to the purring companions on our laps, the story of felid evolution is a testament to the power of adaptation and survival.

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025