The ocean holds some of nature's most extraordinary predators, but few are as mesmerizing—or as violently efficient—as the mantis shrimp. Known for their otherworldly colors and complex eyes, these marine crustaceans possess a weapon that defies belief: a pair of spring-loaded appendages capable of accelerating faster than a bullet. The mechanics behind their strikes have captivated scientists, engineers, and even military researchers, offering insights into biomechanics that border on science fiction.

At first glance, the mantis shrimp's "raptorial appendages" resemble something between a praying mantis's claws and a boxer's gloves. These specialized limbs are divided into two primary types: "spearers," which impale soft-bodied prey with barbed spikes, and "smashers," which deliver blunt-force trauma capable of shattering crab shells or even aquarium glass. It's the latter that has earned the mantis shrimp its reputation as the ocean's most brutal brawler. The speed of their strike is staggering—some species can unleash their appendages at accelerations exceeding 10,000 times Earth's gravity, reaching speeds of 23 meters per second in under 3 milliseconds. To put that in perspective, their punches are faster than a .22 caliber bullet leaving the barrel.

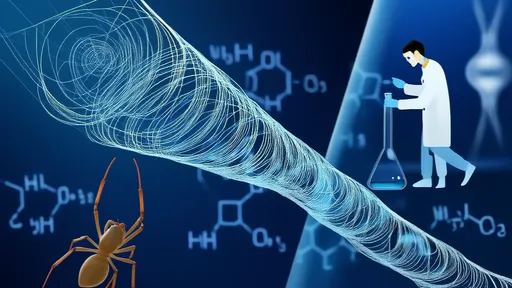

What makes this possible is a biological marvel known as the "click mechanism." The mantis shrimp stores elastic energy in a saddle-shaped structure within its limbs, locking it in place like a drawn bow. When released, the energy uncoils with near-perfect efficiency, bypassing the limitations of muscle contraction alone. This system is so effective that researchers have dubbed it "one of the fastest known movements in the animal kingdom." The force generated isn't just about speed—it creates cavitation bubbles in the water that collapse with such intensity they produce flashes of light (sonoluminescence) and temperatures rivaling the surface of the sun, effectively hitting prey twice: first with the limb, then with a shockwave.

The mantis shrimp's predatory prowess isn't just a curiosity—it's a goldmine for biomimicry. Material scientists study the structure of their appendages, which withstand thousands of high-velocity impacts without fracturing. The secret lies in a helical arrangement of mineralized fibers that dissipate stress, a design now inspiring next-generation body armor and aerospace composites. Meanwhile, robotics engineers are replicating the click mechanism to create actuators that could revolutionize prosthetics or ultrafast machinery. Even military programs have explored adapting the shrimp's cavitation effects for underwater propulsion systems.

Yet for all its engineering potential, the mantis shrimp remains an ecological enigma. How did such a specialized weapon evolve? Why haven't other species developed comparable adaptations? Some researchers theorize that their complex eyes—capable of seeing polarized light and ultraviolet spectra—gave them an evolutionary edge in targeting prey with surgical precision. Others point to their territorial nature; in the crowded reefs where they hunt, overwhelming force may be the only way to secure a meal. What's certain is that this small but formidable creature continues to challenge our understanding of physics, evolution, and the limits of biological design.

As research progresses, one thing becomes clear: the mantis shrimp is more than just a colorful oddity. It's a living testament to nature's ingenuity, where beauty and brutality converge in a single, lightning-fast strike. Whether unlocking secrets of materials science or redefining the boundaries of animal biomechanics, this underwater pugilist reminds us that some of Earth's most advanced technologies have been underwater all along—waiting to be discovered.

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025