The giant panda, with its distinctive black-and-white fur and endearing clumsiness, has long been a symbol of conservation efforts worldwide. Yet beneath its cuddly exterior lies a biological paradox that has puzzled scientists for decades: how did this carnivorous-descended creature evolve to survive almost exclusively on bamboo? The panda's digestive system, teeth, and even its pseudo-thumb all tell an evolutionary story of remarkable adaptation—one that challenges our understanding of dietary specialization in mammals.

The Carnivore's Blueprint in a Herbivore's Body

Anatomically, the giant panda remains a bear—a family firmly rooted in the order Carnivora. Its gut structure, stomach acidity, and short digestive tract are classic hallmarks of meat-eaters, far better suited to processing protein than fibrous plant matter. When researchers first sequenced the panda genome in 2010, they found all the expected genes for a carnivorous digestive system, lacking the elongated intestines or specialized gut bacteria typical of dedicated herbivores. This creates a constant nutritional tightrope walk: pandas extract only about 17% of bamboo's meager nutrients, forcing them to consume 12-15 kilograms daily—a relentless cycle of eating for up to 14 hours each day.

The Dental Revolution

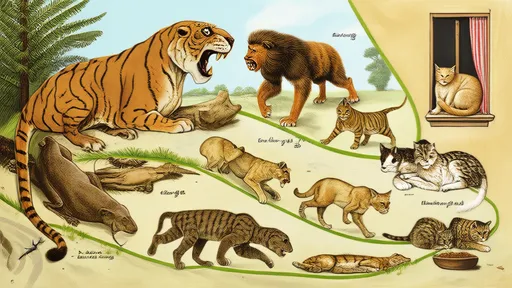

Pandas have undergone one of the most dramatic dental overhauls in mammalian evolution. Unlike their sharp-toothed relatives, pandas developed massive molars with complex ridges—perfect for crushing woody bamboo stems. The jaw muscles anchor higher on the skull, creating extraordinary bite force (comparable to lions) to pulverize tough cellulose. Fossil evidence shows this transition began 2-3 million years ago when pandas shifted from an omnivorous diet to bamboo specialization. Intriguingly, their canines remain large—likely as tools for stripping bamboo bark rather than hunting prey.

Bamboo's Hidden Challenges

This seemingly simple diet is fraught with invisible dangers. Unlike grazing animals that select young shoots, pandas must consume mature bamboo to meet caloric needs, despite its higher silica content—a natural abrasive that rapidly wears teeth down. Compounding this, bamboo species periodically undergo mass die-offs (every 20-120 years depending on species), forcing pandas to adapt to new varieties or face starvation. Their gut microbiome, while more diverse than expected, still struggles to break down lignin, leading to inefficient digestion that produces distinctive greenish, fibrous feces.

The Mystery of the Missing Adaptations

What baffles scientists isn't just how pandas adapted to bamboo, but why they pursued such a nutritionally poor food source in the first place. One theory suggests that during Pleistocene climate shifts, bamboo remained widely available while prey animals dwindled. Another posits that specializing in an abundant but undesirable food source reduced competition with other carnivores. Yet the panda's evolutionary path seems almost counterintuitive—they never developed rumination like cows or cecum fermentation like rabbits. Instead, they "hacked" their carnivore biology through sheer quantity consumption and behavioral adaptations like selective chewing.

The Bamboo Clock

Every aspect of panda physiology operates on a bamboo-driven timetable. Their reproductive cycle syncs with bamboo growth spurts to ensure cubs are born when shoots are most tender. Even their famously low metabolism—about 45% of typical mammalian rates—appears calibrated to their low-energy diet. Recent studies reveal pandas conserve energy through minimized movement and surprisingly small organ sizes relative to body mass. This extreme energy budgeting allows survival on what would be starvation rations for most mammals their size.

Conservation Implications

Understanding the panda's precarious dietary adaptation underscores why habitat fragmentation poses such an existential threat. Unlike true generalists, pandas require specific bamboo varieties at different altitudes and seasons. Climate models predict that by 2070, warming could eliminate 35-95% of current bamboo habitats. Conservationists now emphasize "bamboo corridors" to allow migration between patches—a strategy acknowledging that the panda's evolutionary success may become its greatest vulnerability in a changing world.

The giant panda stands as a testament to nature's improvisational genius—a carnivore that rewired itself to thrive on one of Earth's most challenging menus. Its existence challenges the very definitions of herbivore and carnivore, reminding us that evolution works with what's available, not what's optimal. As research continues, each discovery peels back another layer of this biological paradox, revealing an adaptation story more fascinating than we ever imagined.

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025