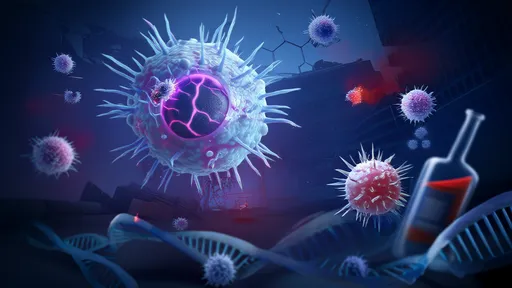

The scientific community stands at a crossroads as gene drive technology emerges as a potential game-changer in the fight against malaria. By forcing genetic modifications through wild mosquito populations, this controversial approach could theoretically collapse entire species of disease-carrying insects. Yet beneath its revolutionary promise lies a simmering debate about ecological consequences that might ripple far beyond mosquito eradication.

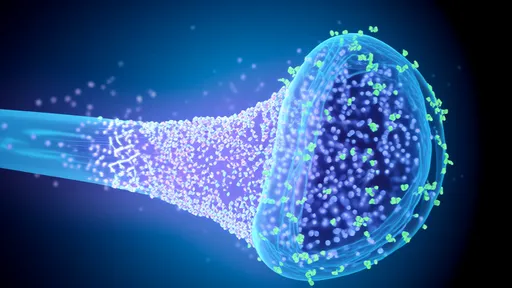

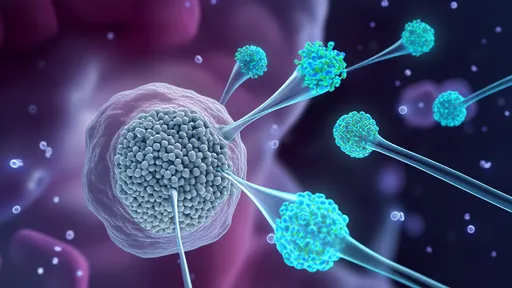

Gene drives represent nature's cheat code - a way to bypass traditional inheritance rules. When engineered into mosquitoes, these molecular constructs can spread desired traits through nearly 100% of offspring rather than the usual 50%. Researchers working on malaria solutions have focused primarily on Anopheles gambiae, the mosquito species responsible for most African malaria transmissions. Laboratory successes already demonstrate how gene drives can suppress or alter wild-type populations within simulated environments.

Proponents argue with infectious enthusiasm about eliminating a scourge that claims over 600,000 lives annually. The technology's precision targeting of specific mosquito species theoretically reduces collateral damage compared to broad-spectrum insecticides. "We're not talking about eradicating all mosquitoes," explains Dr. Eleanor Whitmore from the Target Malaria project. "Just the handful of species that actually transmit human diseases." Mathematical models suggest complete local elimination of target populations could be achieved within about a dozen generations after release.

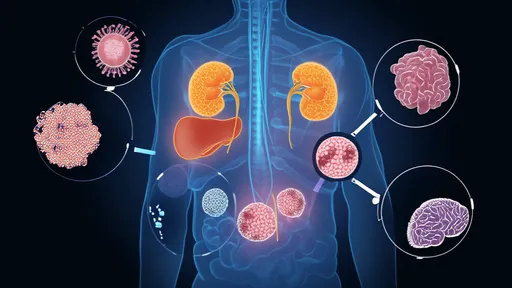

However, ecologists voice profound concerns about unintended consequences that computer models might fail to predict. Professor Kwame Asante from the University of Ghana warns, "We're dealing with complex food webs where mosquitoes serve as pollinators and food sources. Remove one thread and the whole tapestry might unravel." Larval mosquitoes contribute to aquatic ecosystems while adults become prey for birds, bats, and other insects. The sudden disappearance of a widespread species could create ecological vacancies that invasive species might exploit.

The scientific literature reveals troubling knowledge gaps. Few studies have examined how malaria mosquito elimination might affect plant pollination in rainforest ecosystems where some orchid species rely specifically on mosquito pollinators. Research from Harvard's School of Public Health indicates that while adult Anopheles mosquitoes don't constitute a major food source for any single predator species, their removal could still impact biodiversity through subtle trophic cascades.

Regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace with the technology's rapid development. Current biosafety protocols were designed for contained experiments, not for self-propagating genetic elements that could cross international borders. The Convention on Biological Diversity continues to debate whether gene drive mosquitoes should fall under strict precautionary principles given their potential to spread across continents.

Field trials already underway in Burkina Faso have sparked both hope and controversy. Local communities receive extensive education about the technology, but some bioethicists question whether true informed consent is possible for an intervention that may affect entire ecosystems. "When we alter the environment, those changes become compulsory for everyone sharing that environment," notes bioethicist Dr. Rina Kent.

Alternative approaches seek to mitigate ecological risks while maintaining public health benefits. Some research teams engineer mosquitoes to resist malaria parasites rather than eliminating the insects entirely. Others propose creating gene drives with built-in expiration dates or geographic limitations. However, these safeguards often reduce the technology's effectiveness - a frustrating trade-off between ecological caution and disease control.

The economic dimensions further complicate the debate. Malaria costs African economies an estimated $12 billion annually in healthcare expenses and lost productivity. Against this staggering figure, potential ecological damages remain frustratingly difficult to quantify. Insurance models for genetic biocontrol don't yet exist, leaving nations vulnerable to unforeseen consequences without financial recourse.

Indigenous knowledge systems offer perspectives often absent from Western scientific discourse. In several African cultures, mosquitoes hold symbolic importance in creation myths and traditional medicine. The idea of deliberately extinguishing a species conflicts with cosmological views that emphasize balance among all creatures. These cultural dimensions rarely feature in technical risk assessments dominated by quantitative metrics.

As research advances, the debate increasingly centers on risk comparison rather than absolute safety. Public health experts emphasize that current malaria interventions also carry ecological impacts - from insecticide resistance to water pollution from bed net chemicals. "The status quo isn't environmentally benign," argues Dr. Sanjay Gupta from the WHO's malaria program. "We're choosing between imperfect options."

The coming years will prove decisive as scientists develop more refined gene drive systems while ecologists improve predictive models. What remains clear is that this technology transcends simple dichotomies of good versus bad. It represents a profound philosophical challenge about humanity's right to deliberately reshape ecosystems, even for noble purposes. The malaria mosquito may become the first test case for whether we can wield such power wisely.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025