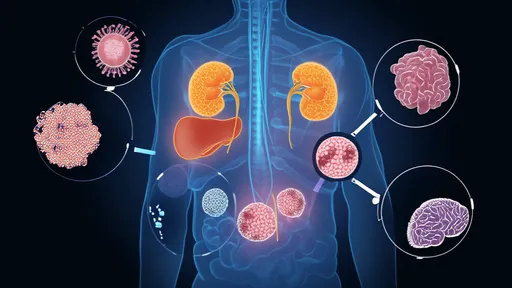

The sharp rise in autoimmune diseases across industrialized nations has become one of modern medicine’s most perplexing puzzles. From rheumatoid arthritis to type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis, these conditions—where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues—are increasing at rates that cannot be explained by genetics alone. Researchers are now turning their attention to a provocative idea: our ultra-sanitized, microbe-depleted lifestyles might be fueling this epidemic. At the heart of this theory lies the hygiene hypothesis, which suggests that early exposure to microbes is crucial for training the immune system. But as societies become more sterile, the consequences may be far more profound than we ever imagined.

For decades, the hygiene hypothesis has been used to explain the parallel rise in allergies and asthma. The premise is simple: children raised in overly clean environments lack sufficient microbial challenges, leading to hyperreactive immune responses to harmless substances like pollen or peanuts. However, the scope of the hypothesis has expanded dramatically. Scientists now suspect that the same microbial deprivation disrupting allergic responses might also be derailing the immune system’s ability to distinguish self from non-self—the hallmark of autoimmunity. This shift in thinking has opened up a new frontier in immunology, one where dirt, parasites, and even harmless bacteria are seen not as enemies, but as essential collaborators in human health.

The evidence supporting this microbial link to autoimmunity is mounting. Epidemiological studies reveal striking disparities: populations living in rural areas or low-income countries with higher microbial exposure have significantly lower rates of autoimmune diseases compared to urbanized, high-income regions. For example, multiple sclerosis is virtually unheard of in certain parts of Africa where parasitic worm infections are endemic, while it’s increasingly common in Scandinavia. Similarly, type 1 diabetes incidence correlates inversely with enterovirus infections in childhood. These patterns suggest that some infections might paradoxically protect against autoimmune disorders by modulating immune function.

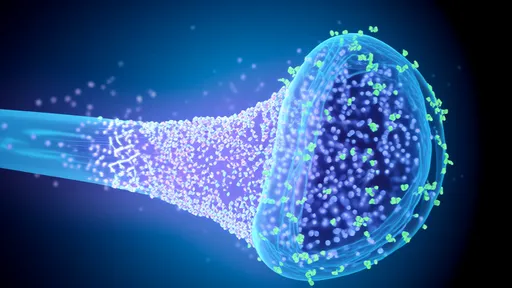

But how exactly does microbial exposure prevent autoimmunity? The mechanisms are complex but revolve around immune education. In early life, the immune system undergoes a process akin to programming, learning what to attack and what to tolerate. Microbes—especially those co-evolved with humans over millennia—appear to provide critical signals that steer this process toward balance. Certain gut bacteria, for instance, promote the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which act as peacekeepers, suppressing excessive immune reactions. Without these microbial tutors, the immune system may become prone to overreacting to harmless stimuli or even turning against the body’s own tissues.

The modern lifestyle has created a perfect storm for microbial depletion. Antibiotic overuse, processed diets low in fiber (which gut bacteria thrive on), excessive C-section births (which skip the microbially rich vaginal passage), and urban environments devoid of soil-based organisms have collectively eroded our microbial diversity. Even something as seemingly benign as antibacterial soap may be stripping away beneficial skin microbes that help calibrate immune responses. The result is what some scientists call “biome depletion syndrome”—a state of chronic dysbiosis that leaves the immune system both overactive and misguided.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence comes from animal studies. Germ-free mice—raised in sterile conditions—develop severe immune dysregulation and are highly susceptible to autoimmune conditions. But when these mice are colonized with specific bacterial strains, their risk plummets. Human interventions, though limited, show similar promise. Small clinical trials using parasitic worm therapy (helminthic therapy) have reported improvements in multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease symptoms, likely due to the worms’ ability to induce anti-inflammatory pathways. Meanwhile, probiotics designed to restore gut microbial balance are being explored as potential adjunct therapies for autoimmune disorders.

Critics caution that the hygiene hypothesis isn’t a blanket explanation. Autoimmunity arises from a complex interplay of genetics, environment, and chance. Not all microbes are beneficial, and some infections can actually trigger autoimmune reactions in susceptible individuals (e.g., strep throat preceding rheumatic fever). Moreover, hygiene practices like clean water and vaccines have saved countless lives—no one advocates returning to the unsanitary conditions of the past. The challenge lies in distinguishing protective microbes from harmful ones and finding ways to safely reintroduce the former without the risks of the latter.

As research progresses, innovative solutions are emerging. “Old friends” hypothesis proponents suggest targeted microbial supplementation—using carefully selected harmless organisms that co-evolved with humans—to restore immune balance. Farms exposing children to diverse animal microbes (the “farm effect”) are being studied as models for preventive strategies. Even urban planning may play a role, with green spaces designed to foster exposure to biodiversity. Meanwhile, precision microbiome therapies, tailored to an individual’s microbial and genetic profile, represent the cutting edge of autoimmune prevention and treatment.

The surge in autoimmune diseases serves as a stark reminder that human health is deeply intertwined with the microbial world. While hygiene has brought undeniable benefits, we may have inadvertently thrown out the baby with the bathwater—discarding organisms essential for our immune systems to function properly. As science unravels these complex relationships, a new paradigm is emerging: one where “clean” doesn’t mean sterile, and where certain microbes are welcomed as lifelong partners in health. The path forward likely lies not in rejecting modern hygiene, but in refining it—harnessing our growing knowledge of the microbiome to build immune systems that are both robust and balanced.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025