The rise of the biohacking movement has ushered in an era where genetic modification is no longer confined to high-tech laboratories. In garages, makeshift labs, and even community spaces, a growing number of DIY enthusiasts are experimenting with CRISPR and other gene-editing tools. What began as a fringe subculture has now evolved into a global phenomenon, raising urgent questions about ethics, safety, and the limits of regulatory oversight.

The allure of democratized science is undeniable. Biohackers argue that genetic engineering should be accessible to everyone, not just institutional researchers. Online forums and open-source platforms have made it easier than ever to acquire knowledge, share protocols, and even order DIY CRISPR kits for a few hundred dollars. For some, this represents a revolutionary shift—an opportunity to bypass traditional gatekeepers and accelerate scientific discovery. Others see it as a dangerous game, where amateurs tinker with life’s building blocks without fully understanding the consequences.

The regulatory landscape, however, is struggling to keep pace. Governments and agencies like the FDA and WHO are accustomed to overseeing pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions, not individual hobbyists. While selling genetically modified organisms (GMOs) or conducting human trials without approval remains illegal in most countries, the enforcement of these rules is patchy at best. A person modifying their own DNA in their home lab, for instance, often falls into a legal gray area. Critics warn that this lack of clarity could lead to unintended ecological disruptions or even the emergence of bioengineered pathogens.

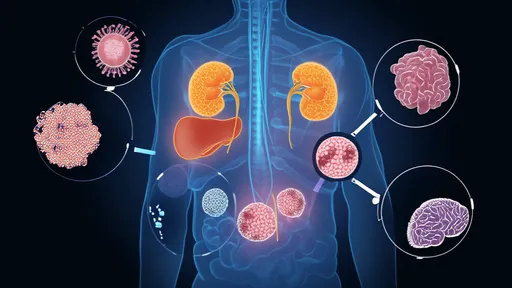

One of the most contentious debates centers on self-experimentation. High-profile cases, such as biohackers injecting themselves with untested gene therapies, have sparked outrage among mainstream scientists. Medical professionals emphasize that CRISPR is not yet precise enough to guarantee safety, and off-target effects could have long-term health implications. Yet, biohackers counter that self-experimentation has historically driven medical progress, pointing to figures like Barry Marshall, who famously drank a culture of H. pylori to prove its link to ulcers. The difference, skeptics argue, is that genetic changes are heritable and far harder to reverse.

Beyond individual risks, there’s the broader question of biosecurity. Could a rogue actor—intentionally or accidentally—create a harmful organism? The 2018 case of a Chinese scientist who edited the genes of twin babies without ethical approval sent shockwaves through the scientific community. While most biohackers are motivated by curiosity or altruism, the potential for misuse remains. Some experts have called for stricter controls on the sale of gene-editing tools, while others advocate for better education to ensure hobbyists understand the risks.

Despite these concerns, the biohacking community shows no signs of slowing down. Grassroots initiatives, like community labs offering safety training, are emerging as a middle ground between innovation and responsibility. Meanwhile, policymakers are grappling with how to foster scientific exploration without compromising public safety. The challenge lies in striking a balance—one that neither stifles the democratization of science nor leaves the door open to catastrophe.

As the lines between professional and amateur biology continue to blur, the world is being forced to confront a new reality: the power to alter life is no longer in the hands of a select few. Whether this leads to a golden age of personalized medicine or a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences remains to be seen. What’s certain is that the conversation around DIY gene editing is only just beginning.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025