The specter of a "superbug apocalypse" looms large over global health discussions as antibiotic resistance escalates from a theoretical threat to a grim reality. The World Health Organization has labeled antimicrobial resistance (AMR) one of the top ten global public health threats facing humanity. What began as medical curiosity—bacteria surviving penicillin exposure in the 1940s—has snowballed into a crisis rendering last-resort drugs ineffective against common infections. The post-antibiotic era, once dismissed as alarmist rhetoric, now features in contingency plans from New Delhi to New York.

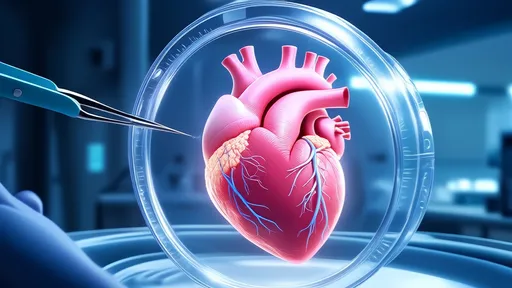

Modern medicine's foundations are crumbling. Routine surgeries, cancer treatments, and childbirth become high-risk procedures without working antibiotics. The 2019 AMR Review estimates 10 million annual deaths by 2050 if current trends continue—surpassing cancer mortality. Developing nations bear the brunt: counterfeit antibiotics, unregulated prescriptions, and poor sanitation create ideal conditions for resistant strains. India's sewage systems teem with resistance genes from pharmaceutical runoff, while Nigerian hospitals report untreatable neonatal sepsis cases. Yet this isn't solely a developing world problem. In the U.S., CDC data shows resistant infections cause 35,000 deaths yearly—more than opioid overdoses.

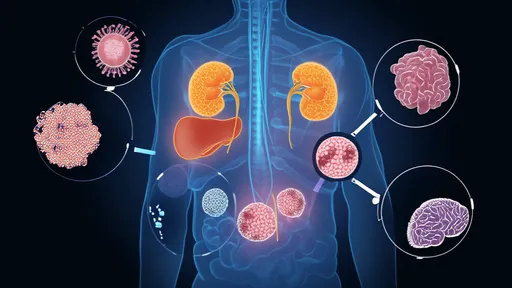

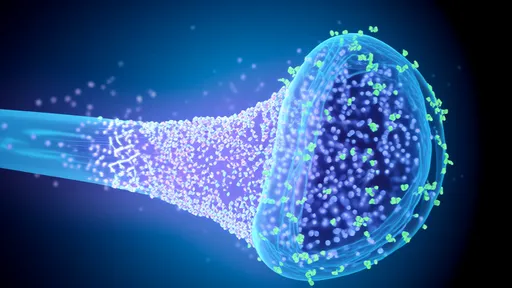

The biological arms race accelerates through disturbing mechanisms. Bacteria employ efflux pumps to expel antibiotics, modify drug targets through genetic mutations, and even communicate resistance via plasmid "instruction manuals." Last year, researchers identified a E. coli strain resistant to colistin—a 1950s antibiotic resurrected as a last defense. This resistance gene, mcr-1, spreads horizontally across bacterial species. Compounding the crisis, pharmaceutical companies abandoned antibiotic development; only two novel classes have reached markets since 2000. The economics are prohibitive: antibiotics require massive R&D investment but generate modest returns compared to chronic disease medications.

Global responses remain fragmented despite escalating warnings. The WHO's Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) represents progress, yet only 109 countries participate. Pharmaceutical giants signed the 2020 AMR Action Fund, pledging $1 billion to develop new antibiotics—but critics note this equals merely three years of Pfizer's Viagra revenue. Meanwhile, agricultural practices undermine medical efforts. America's livestock consume 70% of medically important antibiotics, creating resistant pathogens that jump to humans through food and environmental exposure. The European Union's farm antibiotic ban demonstrates viable alternatives, yet intensive lobbying blocks similar U.S. legislation.

Innovative solutions emerge from unexpected quarters. Ukrainian scientists are repurposing Soviet-era bacteriophage therapies, using viruses that specifically target resistant bacteria. At MIT, researchers developed "living antibiotics" from genetically modified probiotics. Even AI contributes: BenevolentAI's machine learning identified halicin, a novel antibiotic compound, by analyzing molecular structures that evade resistance mechanisms. These breakthroughs, however, face regulatory labyrinths. The FDA's outdated approval protocols favor traditional antibiotics, leaving phage therapy in legal limbo despite its century-old origins.

Behavioral interventions show promise where medical solutions stall. Sweden's "Strama" program reduced antibiotic prescriptions 43% through clinician education and public awareness campaigns. Bangladesh cut childhood diarrhea deaths by training pharmacists to stop dispensing antibiotics for viral infections. Such measures highlight cultural dimensions often overlooked in technical discussions about AMR. The "antibiotic entitlement" mindset—patients demanding pills for every ailment—proves as dangerous as the bacteria themselves.

The geopolitical implications are profound. AMR could destabilize economies as workforce productivity plummets from prolonged illnesses. The World Bank projects $1 trillion additional healthcare costs by 2050 in a high-resistance scenario. Military strategists warn that routine battlefield injuries could again become fatal, reversing a century of medical progress. Some nations treat AMR as national security threats: the UK's 2019 National Action Plan includes surveillance of resistance patterns in foreign countries. This securitization approach risks creating AMR "hotspots" through travel restrictions rather than addressing root causes.

Pathogens recognize no borders, making unilateral actions insufficient. The 2015 Global Action Plan on AMR established a framework for coordinated response, but implementation lags. Developing nations rightly demand technology transfer to manufacture quality generics, while wealthier countries prioritize patent protections. The COVID-19 pandemic offers sobering parallels—vaccine nationalism mirrors the coming scramble for effective antibiotics. One lesson from coronavirus holds particular relevance: early, transparent data sharing about resistance patterns could buy crucial time for containment strategies.

Hope persists in rewired approaches to microbial threats. The "One Health" paradigm gaining traction recognizes the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health. Dutch hospitals now screen patients for resistant bacteria upon admission, isolating carriers to prevent outbreaks. Diagnostic advancements like rapid PCR testing allow targeted antibiotic use instead of prophylactic prescriptions. Perhaps most crucially, younger physicians—raised in the shadow of AMR—prescribe more judiciously than predecessors conditioned by the antibiotic golden age.

The superbug crisis ultimately tests humanity's capacity for collective action. Unlike climate change with visible manifestations, antibiotic resistance unfolds silently in petri dishes and ICU wards. This invisibility breeds complacency even as the clock ticks toward potential catastrophe. The difference between apocalyptic projections and manageable challenge hinges on choices made today—in research labs, policymaking chambers, and community clinics worldwide. The bacteria will continue evolving; the question is whether human institutions can match their adaptability.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025