In an era where science education often feels confined to sterile laboratories and expensive equipment, a quiet revolution is taking place in home kitchens across the world. The Kitchen Laboratory movement has gained remarkable traction, with amateur scientists discovering that their culinary spaces can double as credible research facilities for fundamental biological experiments. Among these DIY science projects, one particularly fascinating experiment stands out – extracting DNA from common household ingredients using nothing more than everyday kitchen items.

The concept might sound like something from a science fiction novel, but the reality is surprisingly straightforward. Every living organism contains DNA, the blueprint of life, and this genetic material can be isolated with basic tools found in any reasonably stocked kitchen. What makes this experiment extraordinary isn't just its simplicity, but how it demystifies complex biological concepts and makes them tangible for people of all ages and educational backgrounds.

At the heart of this kitchen DNA extraction lies a simple scientific principle: breaking down cellular structures to release their genetic material. When professional scientists perform DNA extraction in laboratories, they use specialized buffers and centrifuges. The kitchen version cleverly substitutes these with dish soap (to break down cell membranes), table salt (to help precipitate the DNA), and rubbing alcohol (to separate and visualize the genetic material). The results may not be laboratory-grade, but they're undeniably real – visible strands of DNA that anyone can see with the naked eye.

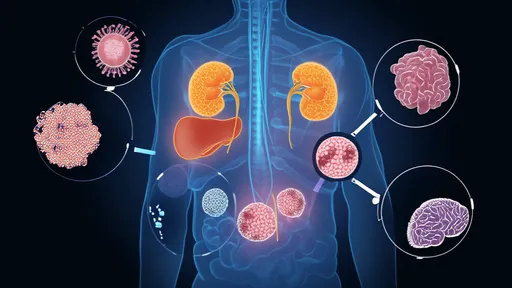

Choosing the right source material is crucial for a successful kitchen DNA extraction. While many guides suggest using strawberries due to their octoploid nature (meaning they have eight copies of each chromosome, making their DNA more abundant and easier to see), adventurous kitchen scientists have successfully extracted DNA from bananas, onions, kiwi fruits, and even their own cheek cells. Each source presents unique challenges and learning opportunities. For instance, human DNA extraction requires gently scraping cheek cells with a toothpick and introduces ethical considerations about handling one's own genetic material.

The process itself unfolds like a culinary recipe with biological consequences. First, the source material must be physically broken down – mashed strawberries or blended bananas work well. Then comes the addition of the extraction solution (salt and soap mixture), which begins dissolving cell membranes. After filtering out the solid particles, the clear liquid is carefully layered with ice-cold alcohol. Within minutes, white, stringy precipitates form at the interface between the two liquids – this is the extracted DNA, a physical manifestation of life's fundamental building blocks.

Beyond the wow factor of seeing actual DNA, this experiment serves as a powerful educational tool. Children who perform it gain concrete understanding of abstract concepts like cells, genetic material, and heredity. For adults, it provides a hands-on refresher of long-forgotten biology lessons. The experiment naturally leads to discussions about what DNA does, how it varies between species, and even the ethical implications of genetic engineering. These conversations often continue long after the kitchen counters have been wiped clean.

Safety considerations remain paramount, even in a kitchen laboratory. While the experiment uses common household chemicals, proper handling is essential. Rubbing alcohol should be used in well-ventilated areas, and all materials should be properly disposed of afterward. Some enthusiasts take additional precautions like wearing gloves, especially when working with human DNA samples. These safety measures mirror those in professional labs, reinforcing good scientific practice even in informal settings.

The implications of kitchen DNA science extend beyond education. Some citizen scientists have taken these basic techniques further, attempting to analyze their extracted DNA with homemade electrophoresis rigs or contributing to community science projects. While these advanced applications require more sophisticated equipment, they all begin with the same fundamental extraction process first tried in home kitchens. This accessibility has helped democratize biological science, making what was once exclusive to well-funded institutions available to curious minds everywhere.

Critics might argue that kitchen experiments lack the precision of professional science, and they'd be correct. The DNA extracted in kitchens comes with proteins and other cellular debris, unlike the pure samples produced in research labs. However, this misses the broader point. The value lies not in laboratory-grade results, but in the demystification of science and the cultivation of scientific thinking. When children (or adults) see those white strands floating in a glass jar, they're not just seeing DNA – they're seeing that complex science is approachable, that mysteries can be solved, and that they themselves can be scientists.

As home science experiments continue gaining popularity, kitchen DNA extraction stands as one of the most accessible and rewarding projects. It requires no special equipment, takes less than an hour, and yields visible, tangible results. More importantly, it represents a shift in how society views science education – not as something that only happens in schools or laboratories, but as an ongoing process of curiosity and discovery that can happen anywhere, even at the kitchen counter while dinner simmers on the stove.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025