Pain is a universal human experience, a biological alarm system that warns us of injury or illness. Yet, a rare subset of the population lives without this sensation entirely. These individuals, often diagnosed with congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP), navigate life unaware of the burns, fractures, or internal ailments that would cripple others with agony. The phenomenon has puzzled scientists for decades, but recent advances in pain genetics are unraveling the molecular mysteries behind this extraordinary condition.

A Silent Mutation: The SCN9A Gene Breakthrough

In 2006, researchers made a landmark discovery while studying families in northern Pakistan where multiple members reported never feeling pain. Genetic sequencing revealed mutations in the SCN9A gene, which encodes a sodium channel (Nav1.7) critical for pain signal transmission in peripheral nerves. Like a broken circuit breaker, these mutations prevent pain signals from reaching the brain. Subsequent research identified over 20 SCN9A mutations linked to CIP across diverse populations, from Japanese families to European cohorts.

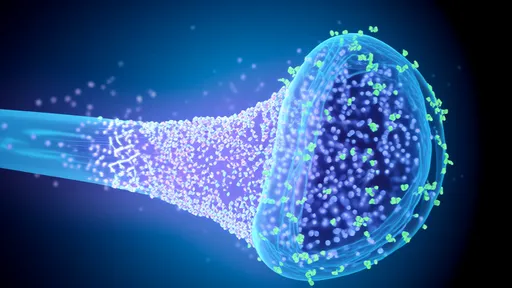

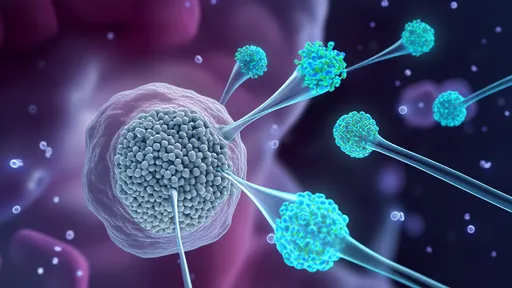

The Nav1.7 channel acts as a gatekeeper in nociceptors—specialized nerve cells that detect harmful stimuli. When functioning normally, these channels open in response to injury, allowing sodium ions to flood the neuron and trigger electrical pain signals. But in CIP patients, the channels remain permanently closed or fail to form properly. Intriguingly, other sensory functions like touch, temperature, and proprioception remain intact, demonstrating pain's unique biological pathway.

Beyond SCN9A: The Expanding Genetic Landscape

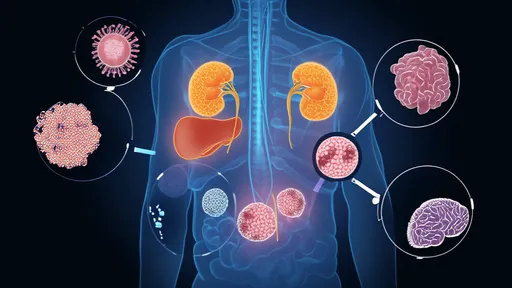

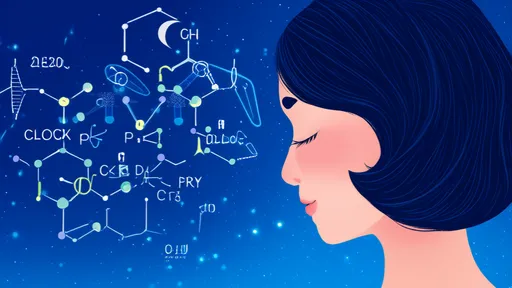

While SCN9A mutations account for many CIP cases, they don't explain all instances of congenital painlessness. Scientists have since identified mutations in at least five other genes (PRDM12, NTRK1, CLTCL1, ZFHX2, and FAAH-OUT) that disrupt different points in the pain perception pathway. The PRDM12 gene, for example, controls the development of nociceptive neurons during embryonic growth. Mutations here leave individuals without the very nerves needed to detect pain.

Perhaps most fascinating is the FAAH-OUT mutation found in a Scottish woman known as "Patient PK." Unlike other CIP cases, PK exhibits accelerated wound healing alongside her pain insensitivity. Researchers discovered that her rare mutation boosts anandamide levels—an endocannabinoid that modulates both pain and inflammation. This unexpected finding has opened new avenues for researching painkillers and regenerative medicine simultaneously.

The Paradox of Painlessness

Living without pain might sound like a superpower, but it's a dangerous condition. CIP patients frequently suffer untreated injuries—bitten tongues in infancy, fractured bones mistaken for sprains, or life-threatening appendicitis detected only at rupture. Many don't survive childhood without vigilant caretaking. Dental injuries prove particularly common, as individuals chew through lips or break teeth without realizing it. The very absence of pain that seems advantageous becomes a constant threat to survival.

Psychological studies reveal another layer: some CIP individuals report feeling socially isolated, unable to empathize with others' physical suffering. They describe frustration when doctors dismiss their condition as impossible or when acquaintances assume they're lying about injuries. The condition challenges fundamental assumptions about human experience—how does one learn danger without pain's teaching? Parents of CIP children often resort to elaborate monitoring systems, checking for bruises, fevers, or behavioral cues that might indicate hidden trauma.

From Rare Disorder to Medical Revolution

The study of pain-insensitive individuals has transformed pharmaceutical research. Drug companies are racing to develop Nav1.7-blocking analgesics that could replicate CIP's effects without its dangers. Early-stage clinical trials show promise for treating chronic pain conditions like erythromelalgia and phantom limb pain. One experimental drug, funapide, selectively inhibits Nav1.7 channels and has shown efficacy in reducing pain from pancreatitis.

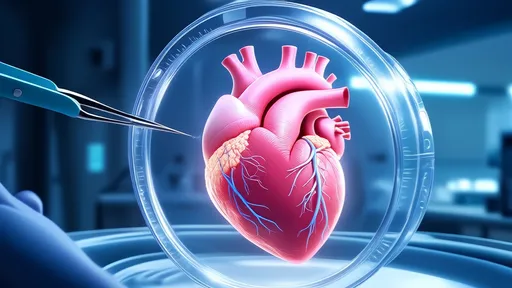

Gene therapy approaches are also emerging. Researchers at University College London successfully used CRISPR to disrupt SCN9A in mice, effectively "turning off" their pain sensitivity without affecting other senses. While human applications remain distant, such breakthroughs suggest a future where severe chronic pain could be edited out at the genetic level. Meanwhile, the FAAH-OUT discovery has spurred investigation into cannabinoid-based healing accelerants.

Ethical Frontiers in Pain Research

As science moves closer to manipulating pain sensitivity, ethical questions multiply. Should gene editing be used to create pain-free soldiers or athletes? Would eliminating chronic pain alter fundamental aspects of human identity and resilience? Some disability advocates argue that rather than eliminating pain, society should better accommodate those who experience it differently. The CIP community itself is divided—while some wish for treatments to feel "normal," others take pride in their neurodivergence.

These questions grow more pressing as genetic testing becomes widespread. Cases of "partial" CIP—where individuals feel reduced but not absent pain—are increasingly identified through DNA testing. Parents now face dilemmas about whether to test asymptomatic children for CIP genes, balancing medical preparedness against potential psychological impacts. The very definition of pain is being renegotiated in genetic terms, challenging centuries of philosophical and medical thought.

Conclusion: Pain's Evolutionary Gift

The existence of pain-insensitive individuals underscores pain's vital evolutionary role. It's not merely a sensation but a complex biological communication system refined over millennia. Each CIP mutation reveals another piece of pain's intricate machinery—from sodium channels to neuronal development pathways. As research continues, these rare genetic variants may hold keys to relieving suffering for millions, provided society navigates the accompanying ethical terrain with equal parts ambition and wisdom.

What remains undeniable is pain's profound role in the human experience. Those born without it don't live charmed lives but face extraordinary challenges, reminding us that even our most unpleasant sensations serve crucial purposes. In studying their genetics, we don't just understand disease—we comprehend what it means to be vulnerably, vitally human.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025